Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Magnetic Poles

Magnets have two poles—one called “north” and the other called “south.” The poles of a magnet have earned these names because hundreds of years ago naturally occurring magnets were used for navigation. When a magnet was freely suspended, it was discovered that one pole naturally pointed towards the Earth's geographic north pole. This was named the "north pole" of the magnet. The end that pointed toward the Earth’s south pole was named, you guess it, the “south pole” of the magnet. Magnets are often referred to as dipoles since they have two poles.

If you play with magnets, you will likely feel that

opposites poles attract and like poles repel.

This is one of the first similarities that we notice between magnetism and electric charges. This phenomenon is what the Ancient Egyptians observed thousands of years ago and what allowed sailors to navigate the seas before GPS. But why does this occur? What makes something a magnet? Let’s explore these questions next.

Magnetic Domains

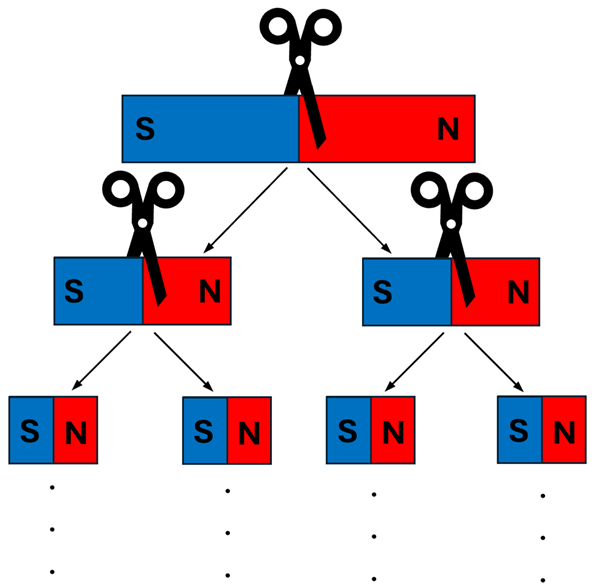

You might think that if you cut a magnet in half, you would get one north pole and one south pole. That is not the case. If a magnet is cut in half, you actually get two magnets. Cutting these in half again gives you four smaller magnets.

Figure 1

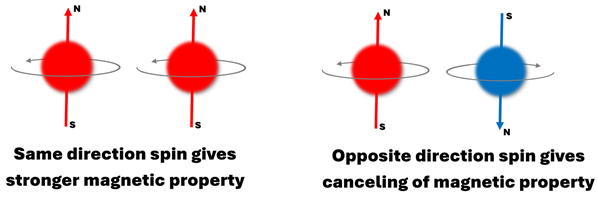

Repeating this process down to the atomic level suggests that atoms themselves are tiny magnets. In fact, every spinning electron is a tiny magnet. A pair of electrons spinning in the same direction make up a stronger magnet. A pair of electrons spinning in opposite directions cancel out each other’s magnetic properties.

Figure 2

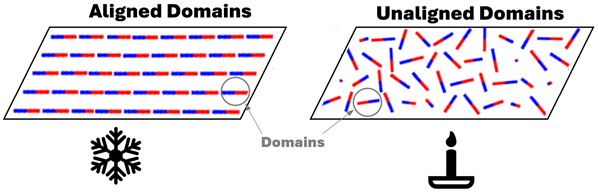

Since opposite poles attract, a group of adjacent atoms typically align so that these tiny magnets are all pointing in the same direction. This group of magnetically aligned atoms is called a domain. What is interesting is that heating up a magnet removes its magnetic properties. This is because all atoms are in motion and have kinetic energy. Since temperature is the measure of the average kinetic energy of these atoms, a hot magnet will be made of domains that are less aligned than a cool one.

Figure 3

Since all matter is made of atoms with electrons, why isn’t everything a magnet? Most atoms have a similar number of electrons that spin in opposite directions. This is why most materials are not magnets. Ferromagnetic materials such as iron, nickel, and cobalt can be permanently magnetized by an external magnetic field that causes the alignment of magnetic domains. Paramagnetic materials such as aluminum, titanium, and magnesium interact weakly with an external magnetic field. For these materials, the domains do not remain aligned after the external field is removed.

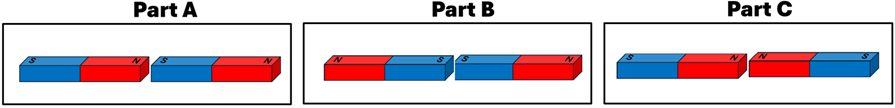

Figure 4

We just saw that cutting a magnet in half gives rise to two smaller magnets rather than a separate north pole and south pole. This means that there are no magnetic monopoles. In other words, you can’t have just a north pole. You can’t have just a south pole. This is one of our first differences between magnetism and electric charges. There are many other similarities and differences between these two phenomena—such as the concept of a field. Our next lesson will explore the important concept of the magnetic field.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Identify which magnet configurations will attract and which will repel.

2. Complete the table by checking the correct claim, evidence, and reasoning.

|

Claim

A: Cutting a magnett in half creates two individual poles.

B: Cutting a magnet in half creates two smaller magents

|

Evidence

A: Regardless of orientation, the two halves would always attract.

B: Depending on orientation, the two halves would sometimes attract and sometimes repel.

|

Reasoning

A: Magnetism occurs at the atomic level.

B: Magnetism is lst when magnets are cut.

|

3. True or False: Heating up a magnet makes it an even stronger magnet.

Figure 1 Source: Earth Icon from Microsoft Word, rest Author Created

Figure 2 Source: Scissors from Microsoft Word

Figure 3 Source: Snowflake and Candle Icons from Microsoft Word

Figure 4 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fridge_Magnet_model.gif